-

Strategic Mobilisation Canvas – New Version Available

-

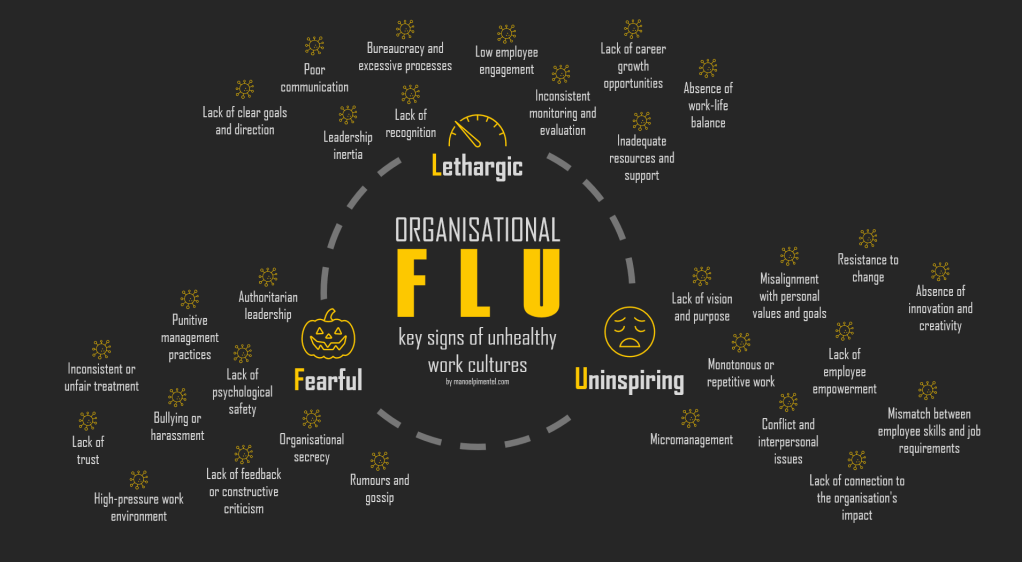

Unmasking the Organisational FLU: Confronting Fear, Lethargy and Uninspiration in Companies

In the corporate landscape, there is a silent but potent affliction we can call Organisational FLU. In this context, FLU is an acronym for Fearful, Lethargic and Uninspiring. It represents a detrimental set of attitudes and behaviours that can cripple companies from within. Understanding the dangers of Organisational FLU is essential, as it undermines employee morale, stifles innovation and hampers organisational growth. This article aims to shed light on the perils of this issue, provide a comprehensive framework for identifying its generating factors and present actionable strategies to prevent and mitigate Organisational FLU.

The dangerous consequences of the Organisational FLU

The Organisational FLU poses a significant threat to the well-being and success of companies. Fearful environments breed a culture of mistrust, where employees hesitate to take risks or voice their opinions, stifling creativity and collaboration. Lethargy manifests as decreased productivity, lack of initiative, and reduced engagement, leading to missed opportunities and stagnant growth. Uninspiring cultures rob employees of passion, purpose and a sense of fulfilment. Resulting in decreased motivation, high turnover rates and decreased organisational performance.

Identifying the generating factors for the Organisational FLU

Identifying the generating factors for the Organisational FLU is vital as it enables targeted interventions to address specific issues within the company. Here are some typical causes of fear, lethargy and lack of inspiration:

1. Fearful Organisations

- Authoritarian leadership – When leaders adopt an autocratic or dictatorial leadership style, it can create a climate of fear. Employees may feel intimidated and fearful of expressing their opinions or making mistakes.

- Lack of trust – If trust is lacking between leaders and employees, or among team members, fear can arise. When employees feel that their actions or decisions will be met with suspicion or punishment, they become apprehensive and fearful.

- Punitive management practices – When organisations have a punitive approach to managing employees, such as excessive discipline or harsh consequences for mistakes, it instils fear in the workforce. Employees may become afraid to take risks or innovate due to the fear of retribution.

- Inconsistent or unfair treatment – When employees perceive inconsistent or unfair treatment in areas such as promotions, rewards, or performance evaluations, it can create a fearful environment. Fear arises from the uncertainty of being treated fairly or equitably.

- Lack of psychological safety – If employees feel that they cannot speak up, share their ideas, or voice concerns without facing negative consequences, fear permeates the organisation. The absence of psychological safety inhibits collaboration, innovation and openness.

- Bullying or harassment – Incidences of bullying, harassment, or any form of abusive behaviour in the workplace generate fear among employees. Fear arises from the threat of mistreatment or retaliation.

- Organisational secrecy – When information is withheld or there is a lack of transparency in decision-making processes, employees may feel anxious and fearful about the unknown.

- High-pressure work environment – Constantly high work demands, tight deadlines, and a culture that emphasizes quantity over quality can generate fear among employees. Fear arises from the stress and anxiety caused by the pressure to meet unrealistic expectations.

- Lack of feedback or constructive criticism – When employees do not receive regular feedback or constructive criticism, they may become fearful of making mistakes or not meeting expectations. The absence of feedback hinders growth and promotes a culture of fear.

- Rumours and gossip – If there is a culture of rumours, gossip, or spreading misinformation within the organisation, it can generate fear and uncertainty. Employees may become anxious about their job security or reputations.

2. Lethargic Organisations

- Lack of clear goals and direction – When organisations fail to provide clear goals, objectives, and a sense of purpose, employees may become unsure about their work’s significance. The absence of clear direction can lead to a lack of motivation and a lethargic attitude.

- Poor communication – Inadequate or ineffective communication channels can contribute to a lethargic culture. When information is not shared promptly, transparently, or in a relevant manner, employees may feel disconnected and unmotivated.

- Bureaucracy and excessive processes – Organisations with excessive bureaucracy, cumbersome processes, or complex decision-making structures can stifle productivity and create a sense of inertia. Employees may feel demotivated and lethargic due to the constant hurdles they face in getting things done.

- Lack of recognition and appreciation – When employees’ efforts and achievements go unnoticed or unrewarded, it can lead to a sense of indifference and lethargy. Without proper recognition and incentives, employees may lack the motivation to put forth their best effort.

- Low employee engagement – A lack of opportunities for employee engagement and involvement can contribute to a lethargic culture. When employees feel disconnected from decision-making processes or are not given a chance to contribute their ideas and opinions, they may become disengaged and unmotivated.

- Inadequate resources and support – When employees do not have access to the necessary resources, tools, or support systems to perform their work effectively, it can create frustration and a sense of lethargy. Limited resources can hinder productivity and lead to demotivation.

- Lack of career growth opportunities – Organisations that do not provide clear paths for career growth and development can create a stagnant and lethargic culture. When employees perceive limited opportunities for advancement or skill enhancement, they may lose motivation and enthusiasm.

- Absence of work-life balance – A work environment that promotes long working hours, excessive workload and neglects work-life balance can lead to burnout and fatigue. Employees who feel overwhelmed by work demands may lack energy and exhibit a lethargic attitude.

- Leadership inertia – When leaders exhibit a lack of motivation, initiative, or fail to provide inspiration, it can have a trickle-down effect on employees. Leaders who lack energy or fail to drive change can contribute to a general sense of lethargy within the organisation.

- Inconsistent monitoring and evaluation – If the organization fails to regularly monitor and evaluate performance metrics, customer feedback, or market trends using data-driven approaches, it suggests a lack of commitment to improvement.

3. Uninspiring Organisations:

- Lack of vision and purpose – When organisations fail to establish a clear vision and purpose that inspires and resonates with employees, it can lead to an uninspiring culture. Without a compelling direction, employees may struggle to find meaning in their work.

- Misalignment with personal values and goals – If employees feel that their personal values and goals are not aligned with the organization’s values, mission, or purpose, it can create a sense of unhappiness and a lack of fulfilment.

- Absence of innovation and creativity – Organisations that discourage or stifle innovation and creativity can become stagnant and uninspiring. When employees’ ideas and contributions are not valued or encouraged, it hampers inspiration and prevents fresh perspectives.

- Lack of employee involvement and empowerment – If employees feel excluded from decision-making processes or are not given autonomy and empowerment to contribute their ideas, it can lead to an uninspiring culture. Employees who lack a sense of ownership and influence may feel demotivated and uninspired.

- Resistance to change – Organisations that resist or are slow to adapt to change can become stagnant and uninspiring. When employees perceive a lack of willingness to embrace new ideas or approaches, it stifles inspiration and prevents growth.

- Monotonous or repetitive work – Engaging in repetitive tasks without opportunities for growth or variety can lead to an uninspiring environment. Employees may feel bored, unchallenged, and disengaged, resulting in a lack of inspiration.

- Micromanagement – When managers excessively control and monitor their employees, it can create a sense of distrust, limit autonomy, and hinder creativity.

- Mismatch between employee skills and job requirements – If employees feel that their skills and abilities are not effectively utilized or that they are not in alignment with the requirements of their role, it can create a sense of unsatisfaction and a lack of fulfilment.

- Conflict and interpersonal issues – When there is a lack of harmony among colleagues, frequent conflicts, or a challenging work environment due to difficult relationships, it can negatively impact employee happiness and satisfaction at work.

- Lack of connection to the organisation’s impact – When employees do not see a direct connection between their work and the organisation’s overall impact or purpose, it can diminish inspiration. Employees who fail to understand the broader significance of their contributions may feel disconnected and uninspired.

Preventing and mitigating the Organisational FLU

By understanding the factors listed above, organisations can implement preventive measures, allocate resources effectively, prioritize employee well-being and improve overall organisational performance. This focused approach helps create a healthier work culture and mitigates the detrimental effects of fear, lethargy, and uninspiration, fostering a more productive and motivated workforce. Let us analyse some ways for preventing and mitigating the organisational FLU.

1. Cultivating a Positive Culture:

a. Foster trust and psychological safety through open communication and supportive leadership.

b. Encourage collaboration, teamwork and idea-sharing to empower employees and build a sense of belonging.

2. Inspiring Leadership:

a. Develop transformational leaders who communicate a compelling vision, inspire by example and provide mentorship opportunities.

b. Implement leadership development programs to enhance leadership capabilities at all levels.

3. Employee Engagement and Recognition:

a. Provide regular feedback, recognition and rewards for individual and team achievements.

b. Create a culture that celebrates innovation, encourages risk-taking and values creativity.

4. Continuous Learning and Growth:

a. Offer professional development programs, training and mentorship opportunities to foster employee growth and career advancement.

b. Encourage a learning culture where employees are encouraged to acquire new skills and share knowledge.

5. Establishing Meaningful Work:

a. Communicate a clear organisational vision and purpose, ensuring employees understand their contribution to the larger picture.

b. Create opportunities for employees to align their personal values and passions with their work.

Summing up

The Organisational FLU is a dangerous ailment that can cripple companies by instilling fear, lethargy and a lack of inspiration. By identifying and addressing the generating factors, organisations can create a thriving culture that fosters trust, engagement and innovation. By prioritizing open communication, inspiring leadership, employee recognition, continuous learning, and meaningful work, companies can inoculate themselves against the Organisational FLU, paving the way for sustained success, employee satisfaction and organisational growth.

Additional reading references

- The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation and Growth – Amy C. Edmondson.

- Peak Performance: Elevate Your Game, Avoid Burnout and Thrive with the New Science of Success – Brad Stulberg and Steve Magness.

- The Culture Code: The Secrets of Highly Successful Groups – Daniel Coyle

- Leaders Eat Last: Why Some Teams Pull Together and Others Don’t – Simon Sinek.

- Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us – Daniel H. Pink.

-

Mental well-being is the real fuel for great organisational performance

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 12 billion working days are lost every year to depression and anxiety costing US$ 1 trillion per year in lost productivity. The World Economic Forum also highlighted that 77% of employees have experienced burnout at their current jobs. Mental health is a serious matter, and all companies must start to create ways for nurturing better mental health at work.

Mental well-being is not only about being happy or completely stress-free. The WHO defines mental health as ‘a state of well-being in which an individual realises his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and is able to make a contribution to his or her community’. Companies must dedicate special attention to this definition as mental health is an essential condition for productivity. The WHO also published an enlightening article titled ‘Mental Health at Work’ listing key risks to mental health on the job:

- Under-use of skills or being under-skilled at work;

- Excessive workloads or work pace, understaffing;

- Long, unsocial or inflexible hours;

- Lack of control over job design or workload;

- Unsafe or poor physical working conditions;

- Organisational culture that enables negative behaviours;

- Limited support from colleagues or authoritarian supervision;

- Violence, harassment or bullying;

- Discrimination and exclusion;

- Unclear job role;

- Under- or over-promotion;

- Job insecurity, inadequate pay, or poor investment in career development; and

- Conflicting home/work demands.

Mental well-being is a complex theme with a vast set of entangled factors and circumstances. For this reason, it is hard to identify root causes and find the right ways to act. The risk factors listed above can leverage awareness about recurring signs and contribute to the review of HR policies and procedures for preventing typical threats to mental health.

According to the American Psychological Association, preparing managers to promote well-being and evolving organisational mechanisms around employees’ needs are also relevant ways for improving mental health in organisations.

Acknowledging that we are not superheroes is another elementary ingredient for maintaining mental health. Companies must stop promoting hero culture and instead create the means to respect and protect our fragile human condition.

The topic of mental health is a mandatory agenda for all companies around the world. However, there are no correct answers to solve this global and complex challenge. Organisations must be proactive in cultivating mechanisms to prevent and navigate any issue regarding people’s mental well-being. As someone who suffered a profound personal loss caused by a severe mental disorder, I can certainly state that it is the most critical issue if your company is willing to thrive in modern society. For this reason, creating honest spaces for conversation about mental health and well-being is my recommendation for managers and leaders. Protecting mental health is inexpensive and will make a positive impact on people’s lives and performance in the workplace. Just try it.

Sources:

World Health Organization – Data regarding health and well-being:

https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/major-themes/health-and-well-beingWorld Health Organization – Mental health at work:

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-at-work

The World Economic Forum – 5 ways to reduce burnout in your workplace:

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/10/reduce-burnout-5-company-actions

American Psychological Association – 5 ways to improve employee mental health:

https://www.apa.org/topics/healthy-workplaces/improve-employee-mental-health -

Avoiding organisational FRAP

Highly competitive business scenarios and the growing pressure for rapid results push companies towards an intriguing phenomenon called Frenetic Random Activity Periods (FRAP). Some typical characteristics of this organisational behaviour are constantly changing priorities, urgent work, frequent war rooms for solving crises, low-quality deliverables, duplicate initiatives and strategic misalignment. This brief piece highlights the dangers behind organisational FRAP and strategies for preventing this tempting behaviour of zooming around like a mad dog.

The challenges

You have probably witnessed a dog running around from side to side in a high-speed manner and changing direction for no particular reason. Science calls this behaviour Frenetic Random Activity Period (FRAP), and it helps dogs burn accumulated energy. I am using this dog behaviour as an analogy for some similar situations I have frequently seen in organisations these days. Economic and political crises are putting companies in the challenging position of fighting for survival. Consequently, companies are engaging in FRAP behaviour quite often to overcome short-term problems and dangers. Sometimes this behaviour is necessary. However, you might have a much deeper problem if your company is doing it excessively. Let’s explore how to identify and navigate three possible interconnected causes of this phenomenon.

- Future-oriented organisational decision-making lacks strategic thinking – Many companies are careless with their organisational moves and investments, and often, their C-level personnel are focused only on short-term results. There is no thought given to the future and no coherent long-term vision. For these companies, the false sense of speed is more important than the direction. We can easily spot this lack of strategic thinking when companies’ main objectives describe things like “grow revenue” or “increase EBITDA by X%”. Mistaking strategy for fixed plans is another symptom of the absence of strategic thinking. Strategy is a living and continuous process; companies should be able to continuously identify changes and adapt their options accordingly.

- Fragile value proposition for customers – Let’s face the undeniable fact that a considerable number of companies are simply delivering poor-quality products and services to their customers. Companies frequently do not pay attention to the real needs of their users. Their products and services are not fit for their purpose or they do not deliver the promised quality levels. These practices put companies in uncomfortable positions in the competitive landscape. Consequently, these organisations are continually fighting crises to avoid revenue loss as many customers leave the company and fulfil their needs by switching to better options.

- Unprepared Leadership – I swear I tried to find a more polite way to say this, but sometimes organisational FRAP is purely due to bad leadership. It’s not just about people who lack leadership experience. It’s about pseudo-leaders who are more interested in generating short-term results and getting their annual bonus at any cost. Leaders should be able to master balancing an organisation’s energy between solving short-term problems and enhancing the landscape of the future. Without this ability, leaders are mere taskmasters for the fulfilment of short-term decisions.

How to navigate these possible causes?

If we scrutinise these three causes, we will find an intriguing pattern of negligence regarding preparation for the future. Many organisations are focused only on today’s problems and are not looking ahead. This is a systemic problem as there are C-level leaders who are only concerned with the businesses’ survivability. Solving urgent crises and stopping losses are certainly important to keep a business healthy. However, leaders must accept the necessity of investing a reasonable amount of time and money today into creating the future. That is the key to evolving any successful company.

Diligence in saying NO is another necessary skill for strategic leaders. Many companies blindly say YES to any opportunity for making easy money in the short term. We saw this during the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to the massive need for more digital services, companies hired more people and grew their capabilities without considering the future implications of those decisions. As the demand for digital services has decreased over the last few months, the same companies are struggling to maintain the oversized capacity they created during the pandemic.

Some final thoughts

Perhaps organisational FRAP is a natural tendency for any company willing to compete in the market. FRAP might be useful in some circumstances because companies must be nimble enough to react to urgent business. Additionally, adopting a constant frenetic rhythm is tempting in modern society and is highly valued in a workaholic culture. However, companies must stop working hard and start working smart. This means leaders should be able to assess, prioritise, and test strategic options for addressing short-term and long-term challenges. Strategic thinking is a key ingredient for developing smarter businesses. I recommend you take a look at the five basic principles described in the article ‘How to mobilise the organisational network toward strategic outcomes?’. Leaders at different levels should be aware of the FRAP phenomenon and should more diligently invest a reasonable portion of their organisational energy towards creating a better future for the business. That is the best antidote to prevent organisational FRAP.

-

Managing Digital Organisations

Creating digital products and services requires more than a set of novel technologies. A different organisational system must be adopted to enable effective digital business operations. As an example, a digital organisation is a company equipped with technologies, processes, policies, structures and behaviours compatible with the need to navigate a fast-changing market and deliver outstanding digital experiences. Key findings from my various experiences over the last decade regarding digital organisations are shared below. This guide is not exhaustive but serves as a compilation of patterns I have identified in companies from segments including banking, telecommunications, gaming, technology, education and digital assets.

The pressure for fast responses and economic efficiency are crucial drivers for creating operating models more suitable for delivering efficacious digital experiences to customers, employees and shareholders. Companies must also be more prepared to face dynamic competitive landscapes introduced by emerging technologies. Consequently, the main changes necessary to face these new challenges must be clarified. The twelve factors listed below can serve as an initial sketch for helping executives and managers to understand the variety of disciplines that must be addressed to navigate the upcoming digital challenges. Let’s analyse each of these key factors.

01 – Focus on customer needs

Digital markets are highly dynamic and unpredictable. Users’ needs are always evolving and becoming more individualised. For this reason, digital organisations must readily employ mechanisms to create customer proximity, value their voice, measure satisfaction and develop pleasing relationship channels. Matching digital and physical needs is another relevant challenge. Quite often, companies must create digital journeys to integrate a large network of partners and facilitate the delivery of physical goods to customers. This challenge is present from big players like Amazon to your favourite small coffee shop around the corner. Techniques such as user research, design thinking and fit-for-purpose are instrumental in shaping better clarity regarding real customer needs.

02 – Use technology to enhance business performance

Technology is the main protagonist in the digital scene as humanity constantly seeks ways to facilitate labour and enhance productivity. All the advancements in AI, analytics, interoperability, scalability, elasticity and mobility have enormous potential to automate a vast array of repetitive and predictable activities. These elements must serve as enablers to the human ability to face complex and fast-changing situations. Thus, digital organisations must revisit their investments in smart technologies to implement solutions more capable of dealing with the need for speed and growth of the business.

03 – Grow awesome teams

Creating high-performing teams with characteristics such as collaboration, autonomy, technical excellence and psychological safety is crucial. An awesome team can establish tight social connections among members and a deep understanding regarding common values, strengths and overall weaknesses. We must also recognise that people have different intrinsic motivators. Traditional formulas are no longer effective for motivating and engaging people. Digital companies must be capable of testing various ways to boost employee engagement. For instance, the well-known study named ‘Project Aristotle’ (from Google) conveyed practical insights into the key characteristics of effective teams. According to this research, ‘Teams are highly interdependent – they plan work, solve problems, make decisions, and review progress in service of a specific project. Team members need one another to get work done’. This concept encompasses the main enhancements necessary to develop high-achieving teams.

04 – Shorten feedback cycles at various levels

In general, digital organisations operate in complex and uncertain environments. Therefore, feedback is the fuel for continuous improvement. Short feedback cycles are about having information available and the ability to constantly sense improvement opportunities in processes, products, behaviours and structures. Having a regular cadence of planning and review contributes to taking the best out of feedback cycles. Note that fast feedback cycles must be adopted at several layers of an organisation to engage in multiple levels of strategic decisions. For this reason, fast feedback cycles are used to continuously review how an action is implemented and also to learn whether the organisation is advancing towards the right strategic aspirations (for example, collecting feedback on the impact of portfolio decisions).

05 – Embody consistent engineering practices

Building digital products and services requires technical mastery in designing, developing, testing, deploying and maintaining modern software and applications. Practices for enhancing code quality and security are also mandatory for delivering long-lasting products. The DevOps culture is also a relevant ingredient for enhancing the entire product development lifecycle. Additionally, a core subject in digital organisations is the implementation of tools to monitor the operational performance of applications and infrastructure.

06 – Creating strategic cohesion among local units

Cohesion is the ability to optimise an end-to-end work system and facilitate integration, alignment and collaboration across multiple teams. Moreover, cohesion means harmonising the autonomy to develop local strategies with global drivers and aspirations. Local units need a sufficient level of autonomy for fast decision-making and delivering value with more speed and accuracy. Running Strategic Mobilisation Sessions (LINK) is an excellent example of how to foster more cooperation among various units and create more alignment regarding shared objectives and constraints.

07 – Weakening the walls between silos

Working in silos is an inevitable social construct in large organisations. Even when we tried to break them down, we ended up creating only different forms of silos with fancy terminologies. For this reason, digital organisations must find ways to promote cross-functional collaboration among different areas and departments. That is why sometimes we don’t need to break the silos; we just need to enhance their connectivity. These ties can be encouraged by running shared initiatives. Transparency regarding relevant decisions and data is an essential ingredient for improving the integration between organisational units.

08 – Tame value networks

Delivery of more value with fewer inefficiencies is a frequent topic in executive agendas. Finding ways to reduce queue time, quality variance and unnecessary activities might be levers for achieving better economic results. However, old-fashioned ways of visualising and managing value streams are no longer enough to master the hyperconnected digital world. Value flows to and from several directions in digital organisations. We require dynamic and responsive ways to manage and improve a vast tissue of nonlinear processes, stages and players necessary to run effective digital businesses. Measurements regarding internal efficiency are equally important to raise awareness of optimisations in processes and structures.

09 – Evolve around data

What can’t be measured, visualised and analysed can’t be improved. For this reason, implementing mechanisms for capturing and democratising relevant data is vital to enable fast decision-making on how to improve digital products and services. The ability to use data to extract weak and strong signals is another crucial skill for identifying trends and better strategic moves. It is relevant to underline, continuous processes for capturing and analysing data will also contribute to monitoring financial figures and economic performance.

10 – Create safe spaces for experimentation

Running experiments is the foundation for acquiring empirical learning and it is a powerful way to create innovative products and services. Experiments can succeed or fail, and failure can be frequent when companies validate fresh business hypotheses. Managers should therefore create guardrails for tolerating failures caused by new experiments. Reframing the meaning of failure as a natural part of organisational learning is also essential. People should feel free to take risks and create new ideas. This type of organisational construct is a necessary arrangement for shielding the company’s reputation and growth.

11 – Maintain legal and ethical congruence

Digital operations must not harm people’s rights or well-being. Compliance with regulations, legal responsibilities and ethical requirements is a mandatory characteristic for digital businesses. Users can be a fragile part of the intense relationship with digital products. Companies should be vigilant against any type of abuse and exploitation in their interactions with customers. The same level of concern should be applied regarding employees, shareholders, regulators and partners.

12 – Contextualise management systems

Large organisations typically have a variety of contexts and domains. Companies are social systems with dynamic situations. Problems sometimes require ordered and linear solutions; however, complex issues frequently appear. Navigating complex situations requires nonlinear and unpredictable approaches for iterating and adapting a solution. Managers should be able to sense the nature of challenges and tailor the management system for more coherent outcomes. Occasionally, managers can rely on well-defined and prescriptive practices. Other times, however, the same managers must adopt flexibility and responsiveness in testing new ways to solve complex problems.

Click for zoom in In sum

This list acknowledges the need to address various subjects and capabilities for enabling effective digital organisations. Digital transformation is not only about implementing new technologies. Novel methods of running operations, different behaviours and nimble organisational structures must be considered to achieve excellence in the digital world. An integral and holistic view is necessary to master all the domains in such a deep evolution.

This list above represents a humble point of view based on my experiences over the years. These factors are also accurate considering the executive agenda of most of my current clients. This list of factors is in no particular order—managers and executives can address these factors in several ways.

By sharing this list, I aim to collaborate with other executives and managers to amplify their understanding regarding what a digital organisation is and the key subjects to which firms must dedicate their attention and energy. I hope you find it useful, and you are welcome to tailor these factors to your own context.

-

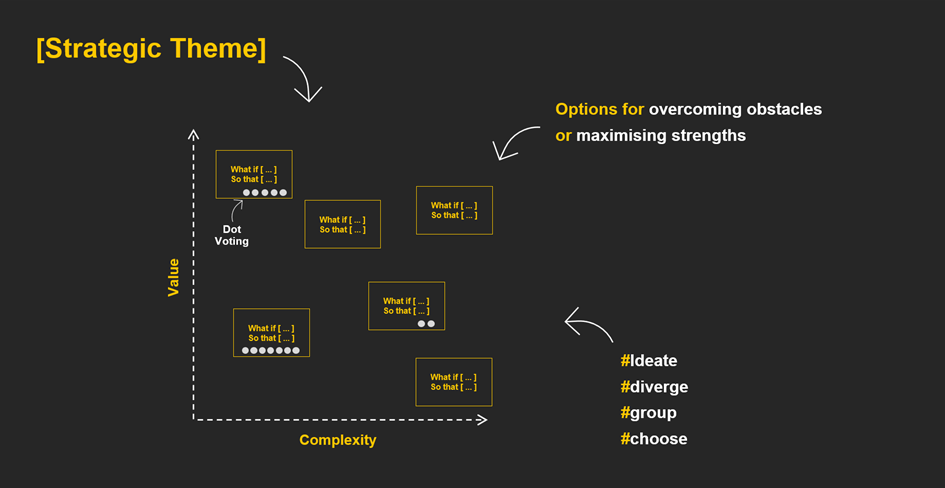

Creating valuable strategic options with the WIST structure

As described in the first article on the Strategic Mobilisation Canvas, strategy is the process of creating the right choices to achieve your business and corporate aspirations. In this article, we will explore an effective technique that I use to create and select the best options when making strategic decisions.

The technique I will share is a complementary approach to the ‘What If’ section in the Strategic Mobilisation Canvas. It effectively embodies the five principles underlying the canvas, with a particular highlight on principle number two – ‘Creating choices rather than a fixed plan‘. More information about the canvas can be seen at the previous post.

People often struggle to create tangible and valuable ideas during ideation activities. Participants tend to be held back by weak ideas and unclear, wishful thinking regarding their business goals and drivers. Therefore, to overcome this challenge during strategic sessions, I invited participants to create options using the text structure of ‘What If–So That’ (WIST) questions.

These two elements combine in the following structure:

What if [we perform a specific option]

So that [a potential benefit or impact is consequently gained].This structure derives from techniques like design thinking and user story writing. It is a simple and useful tool to encourage participants to think about new, valuable possibilities. Here are a few examples of using the WIST structure to devise strategic initiative options:

- What if we establish strategic partnerships with smaller local companies so that we could reduce our response time and save operational costs in our services?

- What if we strengthen our brand awareness and market positioning regarding B2B services so that we can leverage more business opportunities for value-added services?

- What if we hired people from the wider LATAM area outside Brazil so that we increase our capability readiness and improve our cost of delivery?

- What if we acquire a small company with proven experience in a particular sector so that we will accelerate our portfolio expansion and revenue source diversification?

This text structure encourages deeper conversations regarding perceptions of the value and complexity of each strategic idea. Additionally, it gives more substance to identifying effective strategic moves in a given theme, as demonstrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 – Ideation process based on WIST options. It is important to recognise that the options can be evaluated against a different set of scenarios to prioritise and select the best ideas to be implemented. Scenario planning will be covered in further detail in future blog posts.

Developing viable and impactful strategies is challenging and doesn’t happen overnight. A reasonable amount of effort is needed to identify signals, trends, opportunities, threats, and capabilities. Collecting these types of information is vital for preparing and enabling ideation exercises during strategic sessions. With these elements in place, the participants will be more adequately equipped to develop elaborate strategies using the WIST structure.

The WIST structure helps to overcome the difficulties in creating tangible and valuable ideas. It allows the user to navigate obstacles and maximise their existing strengths to develop winning strategies. Additionally, they will have more information to decide on the best options for a given scenario. I hope you find this approach useful as well. Please feel free to use the WIST structure yourself to create more effective strategic moves in your own contexts and business themes.

- What if we establish strategic partnerships with smaller local companies so that we could reduce our response time and save operational costs in our services?

-

[Video] Key lessons about strategic mobilisations in a multinational company

Video recorded during my talk at the Agile Trends Festival 2022.

FE4 – EN – Manoel Pimentel – Key lessons about strategic mobilisations in a multinational company from Agile Trends on Vimeo.

-

Strategising in mutable business scenarios

Photo by WrongTog on Unsplash My previous post regarding strategic mobilisation triggered people’s curiosity about the tool and the principles I introduced in that text. I have received many messages asking for more details and information. Inspired by these positive comments and requests, I explore further in this blog post the implications of strategising in dynamic and mutable scenarios.

The ability to navigate in fast-changing contexts is an essential skill for developing successful strategies, and many clever people have studied how to manage complex, volatile and uncertain scenarios. Thus, there is rich research, experiment and theorising occurring in these fields. I don’t aim to make this blog any kind of scientific article; my intention is to share some ‘lessons from the trenches’ about navigating mutable business situations.

First things first: What does mutable mean in the context of corporate business strategy?

Avoiding the temptation to use fancy scientific language, let’s stick to a simple definition for this key concept. According to the Cambridge dictionary, ‘Mutability’ isthe ability to change or of being likely to change. To be honest, we don’t need to theorise much further than that to understand what we must do to navigate this type of scenario.

Based on this definition, I am experiencing several different mutable situations in my own daily life as an executive. Here are some examples of high mutable situations that I face regularly:

- Competitors’ moves

- Changes in client structures and roles

- Team composition

- Unwanted staff turnover

- Impact of corporate decisions on employees’ intrinsic motivators

- Client’s individual needs and requirements

- New demands

- Revenue performance

- Stock moves in global markets

Importantly, being mutable doesn’t mean being out of control or chaotic. It’s a simple acknowledgment that one can’t always predict when and how something may change. There are things in business less mutable, for sure. I will tackle these particular scenarios in future blogs; right now I’m focusing on how to deal with mutable things in this text.

Keep options open – and your organisational senses

Strategising is about making choices. In business, strategy is a continual process of formulating options and choosing the right one for a given situation.

We can consider different heuristics, or the simple rules people use for facilitating the decision process, when making choices. However, sometimes our choices are not right, even when we have all the information we need, or when we have had previous experience in similar circumstances. The likelihood of being wrong is high when we operate in dynamic situations, as the parts are always moving and creating non-linear connections.

The illusion of being right can harm good strategy development. Awareness of the possibility of being wrong is the paradox of succeeding in business (I learned that lesson in the worst possible way many years ago). That is why companies must have a management system capable of sensing when a chosen option is not the right one, to respond quickly to formulate or adapt other options in a particular situation.

Shortening the feedback cycle about business performance is a key ingredient to deal with mutable and dynamic scenarios. It’s not about adopting any particular framework or method; it is about the attitude of continually planning, learning and adjusting the route when necessary.

Merging strategy and execution

The separation between strategy and execution is probably where the biggest misunderstanding in the management field occurs. I’m not saying companies shouldn’t have hierarchical structures; I’m acknowledging that there is no difference between strategy and execution from a practical point of view.

Strategy continues to happen throughout execution. Strategy is not just about creating plans and stratagems. It is about making the best decisions possible based on known and unknown events. In this case, there are moves we can prepare for in advance, and there are other moves we will only discover when a new circumstance arises. For this reason, strategy should be a continual and distributed process in companies, and it is the best instrument for navigating dynamic and mutable contexts.

Here are some tips for merging strategy and execution, humbly offered:

- Adopt short cycles for creating and reviewing strategic moves

- Talk about strategy every day, not just once a year

- Think about strategy with everyone in your environment, not only with the leaders

- Democratise relevant data and information to empower people to evolve the strategic drivers

- Don’t make the plan the protagonist while you are still creating, reviewing and adapting the strategy

- Keep the strategic process simple and accessible – you don’t need a PhD from a prestigious university to develop winning strategies.

Now it’s your turn

I’ll share more of my experiences about strategy and management systems in forthcoming texts. In the meantime, I invite you to reflect deeply on whether you are developing suitable strategies for navigating mutable environments by acknowledging that you can’t predict and control all the outcome of your strategic moves. For me, this is the most valuable takeout message.

Some relevant references:

Lafley, A.G.; Martin, Roger; Martin, Roger L.. Playing to Win . Harvard Business Review Press. Kindle Edition.

Lustig, Patricia. Strategic Foresight: Learning from the Future . Triarchy

Press. Kindle Edition. Mitchell, Melanie. Complexity. Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition.

-

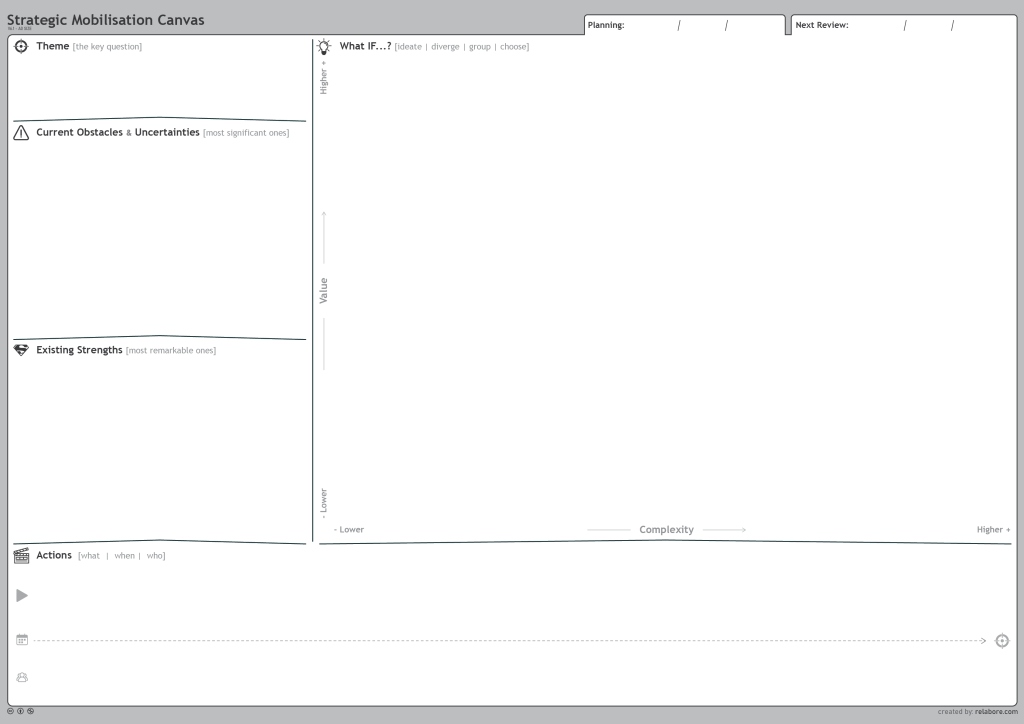

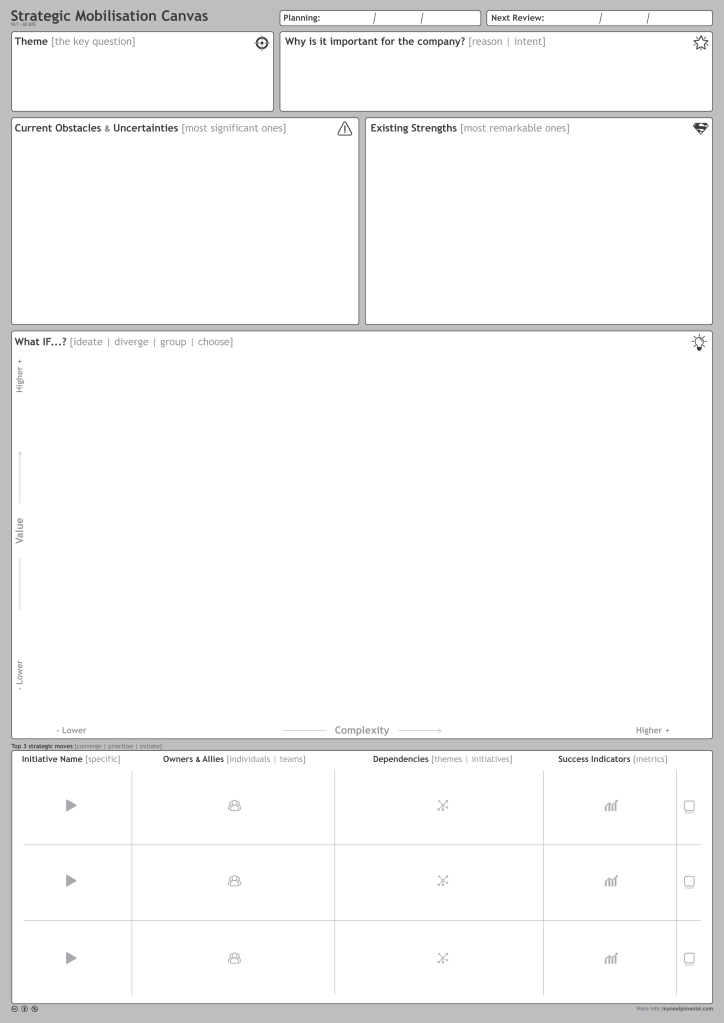

How to mobilise the organisational network toward strategic outcomes?

Clarity, cohesion and responsiveness are essential for survival in the contemporary business landscape. Developing these capabilities isn’t easy and companies need ways to enable strategies for innovating and evolving continuously. Multi-actor collaboration and short feedback cycles are enablers for continuous strategy development. I have been combining these enablers in a tool named Strategic Mobilisation Canvas. Increasing engagement and alignment are recurring benefits I have observed when using this canvas. My greatest aim with this text is to share a pattern of activities and concepts that worked well when facilitating and leading collaborative strategy sessions. I believe these patterns will be helpful for people on a similar journey.

A typical challenge

I often use this approach when companies seek to engage people and align strategic themes. Creating a shared understanding of investing organisational energy is one of the key ingredients for winning strategies. It is about effectively mobilising individuals, teams and communities for developing and deploying a contextualised strategy for corporate and business aspirations.

I apply this canvas to facilitate strategic conversations among executives, board members, directors and leaders. Sometimes, these people don’t need to create the entire strategy thinking from scratch. They only need some help to understand their intent, obstacles, strengths and choices to ignite effective strategic moves towards relevant outcomes. That is the focus of this tool.

Basic principles

The canvas has evolved as I have tried different formats, media and sections. Despite the tool’s form, some underlying principles emerged as patterns in sessions I have facilitated over the years. For this reason, let’s explore some of these principles and dig into the canvas details.

- Principle 1: Collective intelligence is the best antidote for tackling complex problems — Connecting different perspectives and experiences is the most effective way of better comprehending the full spectrum of challenges and opportunities in a highly-dynamic context. That is why the strategy process shouldn’t be done in isolation by only a few people at the very top of the company. The strategy process should be an open conversation and must engage a diverse set of people from multiple areas and levels of the company.

- Principle 2: Creating choices rather than a fixed plan — Strategy is a broad subject with multiple views, theories and techniques. Many leaders and executives wrongly associate the preparation of a plan with the proper process of strategising. In simple words, a plan, as a document, describes the step sequence to achieve something. However, strategy is much more than this. According to professor and author Roger Martin, “strategy is a set of interrelated and powerful choices that positions the organisation to win.” This concept acknowledges that there are elements we can’t control in business and an iterative process is required to validate and adapt the options as it evolves. For this reason, instead of relying only on a fixed action plan, organisations should be able to continuously iterate and adjust the strategy to maximise the winning chances.

- Principle 3: Divergent thinking is an enabler for creativity — Strategy is a continuous creative process for addressing business problems and opportunities. For this reason, having tools and models for facilitating this creative process is essential for developing good strategies. I have used divergent thinking as a platform for creativity during strategy sessions. It has been a helpful approach because it inspires people to create different and diverse ideas. People are also stimulated to diverge regarding each idea’s importance and implementation complexity. It’s an excellent way to nurture collaborative thinking and generate out-of-the-box ideas effectively during a session.

- Principle 4: Think in the long term but act and revise in the short term — Long-term visions and aspirations are essential for companies. However, leaders must be able to take concise actions to learn and refine the strategy continuously. The business landscape tends to be unpredictable, so companies should be able to organise short and narrowed initiatives to collect fast feedback regarding directions and needed adjustments. The Strategic Mobilisation Canvas fosters this approach by inviting people to prioritise feasible initiatives to fit into short work cycles (between one and three months).

- Principle 5: Strategy is a continuous and multidimensional process — Thinking about strategy as something done only by executives or as an activity done once a year is the greatest mistake a company can make. Strategy happens every day and everywhere in the company. Effective strategies amalgamate corporate aspirations, business capabilities and attitudes towards winning choices. For this reason, any strategy session is only a moment to use all the data, research, facts and insights available throughout the organisational tissue. We must do this homework before, during and after the sessions. That’s why the Strategic Mobilisation Canvas promotes a democratic space for ideating, diverging and converging the collective intelligence obtainable in a company.

These principles are the culmination of years of dealing with strategic conversations and decisions in different companies around the globe. They are not exclusive to the Strategic Mobilisation Canvas. Instead, those principles acknowledge some patterns underlying the most successful organisations I worked in during my professional life. Feel welcome to extend these principles to your context as needed.

A canvas for nurturing effective conversations around strategic themes

The Strategic Mobilisation Canvas (see image below) is a tool for engaging people and promoting a better conversation flow regarding strategic questions for an organisation. This canvas is typically applied for facilitating immersive sessions for mobilising people around the activities of:

- Analysing the current strategic scenario.

- Ideating options for building new capabilities and behaviours.

- Prioritising the most valuable initiatives for achieving results in a given theme.

The Strategic Mobilisation Canvas is organised into several critical sections. Let’s explore and dig deeper into these elements.

Theme

Strategy involves mobilising organisational tissue to address relevant corporate and business questions. Therefore, the first section in the canvas regards visualising the major subject the group will strategise about. Each canvas is oriented to only one theme. If necessary, the facilitator can set different breakout sessions according to the number of existing themes. In this case, the participants will use multiple canvases during the whole process. It is also relevant to note that creating strategies toward a particular key result is a typical example of a theme if your company is applying the Objective and Key Results (OKR) model.

Why is it important for the company?

This is perhaps one of the most impactful sections because it promotes alignment regarding the reasons for and intentions behind any particular theme. A clear sense of purpose can bind people together. In this section, the participants should agree on why addressing that question is valuable to the company.

Current obstacles and uncertainties

This section will invite the participants to analyse the current reality to identify the most significant obstacles and uncertainties. Understanding notable impediments and the things we can’t predict is vital to identifying contextualised options for minimising challenges or navigating uncertainty.

Existing strengths

Every company has remarkable traits and capabilities for creating value and achieving results. Leaders should be aware of these characteristics as enablers for creating superior performance. In this section, participants will identify the most relevant strengths the company can employ for navigating a given theme. Sometimes, enhancing existing strengths is much more effective than trying to minimise weakness or develop new capabilities from scratch.

What if?

As stated in the second principle, companies must focus on creating choices rather than a fixed plan for identifying better options for navigating dynamic scenarios and achieving superior results. This section will promote a conversation space for collecting ideas and creating consensus on the collective perception of value and complexity for each discussed option. Perhaps, this section will require the most extended amount of time in the session as it will encourage a safe space for ideating, diverging, grouping and selecting the best choices for materialising strategic moves in the organisation.

Top 3 strategic moves

After the participants carefully analyse the options, this section aims to generate convergence about one or three initiatives the organisation will take per each strategic theme.

Probably you are asking yourself why there are so few initiatives. Generally speaking, each strategic move is a cross-area initiative that will mobilise multiple individuals and teams. For this reason, it is tough to have enough capacity to handle too many organisational actions at the same time. Acknowledging this fact is the key to avoiding the overloading of unfinished ideas across the company.

Another significant benefit I’ve been observing is that people are more diligent in selecting valuable initiatives when there is some limit regarding the number of moves the organisation can handle simultaneously. Prioritisation is the secret recipe for the best use of the existing resources and energy to develop strategic intentions.

The image below shows a short example of a use case of these sections.

Example of the canvas in action Wrapping this up

Strategising should be a living and continuous element in organisations. However, traditional management approaches tend to foster the preparation of high-detailed strategies based on long-term plans described in large documents and created in isolation behind closed doors by executives on the top of the corporate food chain. These approaches are no longer suitable for highly dynamic scenarios as companies need more operational and strategic responsiveness. For this reason, the Strategic Mobilisation Canvas is only a single tool for creating a welcoming environment for engaging people in this journey.

You can download the PDF version here (in the A0 size). Additionally, there is a PNG version in case you need to use it in digital applications like Miro or Mural.

I wish this canvas would be as helpful for you as it has been to me. Feel welcome to drop me a message regarding questions or feedback on this tool.